The Coming Populist Revolt

Populism occurs when the masses revolt against the elites’ view of the world. Elite opinion does not often deal directly with popular opinion, that is, with the people who have to pay for elite opinion. When elites get it wrong, the masses revolt through the ballot; the Voice referendum being a good example. The question is, when is the next chance?

Currently, the elite consensus on issues like net zero, immigration and identity politics is so far removed from the reality of the masses that it is no wonder they are pushing back. The populist revolt, should it occur, will play out at three levels – international, national and personal.

International

Net zero is a preposterous notion. The world population is eight billion people. By 2050, it could be 10 billion people, a 25 per cent increase. These people will need energy. World energy consumption is 600 BTUs. By 2050, it could be 900 BTUs, a 50 per cent increase: more people, higher living standards, more energy. Electricity generation will rise mainly in the Asia-Pacific among developing nations. Renewables do not generally feature in developing countries’ energy mixes anywhere near developed nations’ proportions.

Women have gained formal and substantive equality in Australia.

Of 144 nations tracked for net zero, only 26 have placed in law their commitment to net zero by 2050 (or sooner). For example, the Maldives has pledged net zero by 2030 but it has no plan or accountability mechanism; it is pure hot air. Even Goody Two-Shoes Finland leaves out aviation and shipping and has plans but no mechanism for carbon removal. The US (2050), Russia (2060), China (2060), India (2070) and Brazil (2050) have a ‘policy document’, but nothing in law.

Australia has a plan written in law that is sure to kill the nation’s wealth. Industrial and economic mayhem, loss of reliable energy and higher energy prices will reduce living standards. Minister Bowen’s deployment targets are logistically impossible in the time frame.

Kenneth Schultz estimates a total cost of $1.4 trillion for the Coalition’s renewables-nuclear option. He estimates the cost for Labor’s renewables-battery option at $4.4 trillion, nine times the federal government’s total annual revenue.

National

Migration in Europe and Australia is dangerous at levels that challenge national unity. Numbers count. If one million Palestinians settled in Australia in a short period, for example, the result would undermine Australian society. Palestinians would settle in a few suburbs and recreate a Palestinian society, i.e. one that recreates the hatred extant in Gaza and the West Bank.

Values also count. Australia would do well to distinguish migrants by the nature of their observance, which is apparent in the laws on marriage, succession, or rape in marriage among our key Islamic migrant source countries: Lebanon, Pakistan, Indonesia and Malaysia. A striking feature of those laws is that they distinguish the application of the law by religion. Religion first; the rule of law second. The question is how to distinguish this at an individual level. Classing people by source country is too crude and unfair, but not to distinguish people would be foolhardy. Why should Australia invite those unlikely to integrate or, worse, become an enemy?

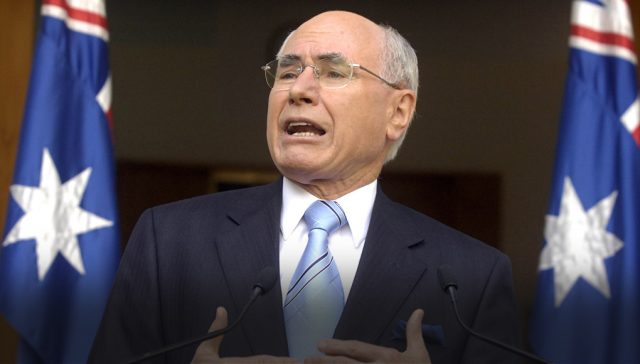

Those who appreciate the benefits of the nation-state would support Prime Minister John Howard’s view that, ‘We will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come.’ Howard and the Australian electorate recognised that some people are not welcome as they are unlikely to fit in. In the long term, Australia will be much more Indian and Chinese. Of the three million permanent migrants who arrived in Australia since 2000, almost 450,000 were from India, and nearly 350,000 were from China. The assumption of integration must be reinforced.

The easy assumptions of integration post-World War II no longer hold. Since 2022, the Netherlands has required a substantial investment from a person applying for permanent residence before that privilege is granted. The civic integration requirements are set out in the Civic Integration Act 2021. The point of the Netherlands law is that applicants must be sufficiently integrated before they become permanent.

The populist revolt, should it occur, will play out at three levels – international, national and personal.

Personal

Women have gained formal and substantive equality in Australia. They are free to sing the praises of Palestine. Homosexuals are free to marry and raise children. But the trans lobby wants to abolish gender, which is dangerous to the mental health of trans people. Sex must be understood in evolutionary terms. There must be sperm and eggs for reproduction. Two women do not create a child, and two men do not create a child. They may care for them, and we wish them well. The proposition that sex is not binary, that it is socially determined, is dangerous, especially to those who find that they are not at ease with their sex and want to reassign their sex to suit their ‘gender’.

Anyone should be free to express themselves as male or female. But when sex is detached from reproduction, there are consequences. As Zachary Elliott argues in Binary: Debunking the Sex Spectrum Myth, ‘If we abandon sex as an important category in our society, how can we conduct safe and effective medical research and treatment; fight sex-based injustices; record accurate crime statistics; maintain fair, safe, and competitive sports categories; and implement equal opportunities for both sexes?’

There is a claim that almost two per cent of the population is intersex, neither male nor female. The numbers consist almost entirely of those who suffer developmental disorders, such as late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia. People with these conditions account for nearly all the males or females who do not appear to be one or the other. The disorders occur in nature and do not result in good health. They are not socially determined.

Populism in the service of correcting the madness of net zero, overplayed migration and undermined sexual identity are ground zero for the populist fightback. The masses await the right leader and the right policies. Populism? More please!

Gary Johns is Chairman of Close the Gap Research

This article was first published in The Spectator.

Dr Gary Johns served as former Assistant Minister for Industrial Relations, Special Minister of State & Vice-President of the Executive Council in the Keating Labor Government. A philosophical rethink saw him accept a series of appointments in the service of economic rationalism, including Senior Fellow at the IPA and Assoc. Commissioner at the Productivity Commission. He recently served as Commissioner of

the Australian Charities and Not-For-Profits Commission.