Resisting centralist power – Part 2

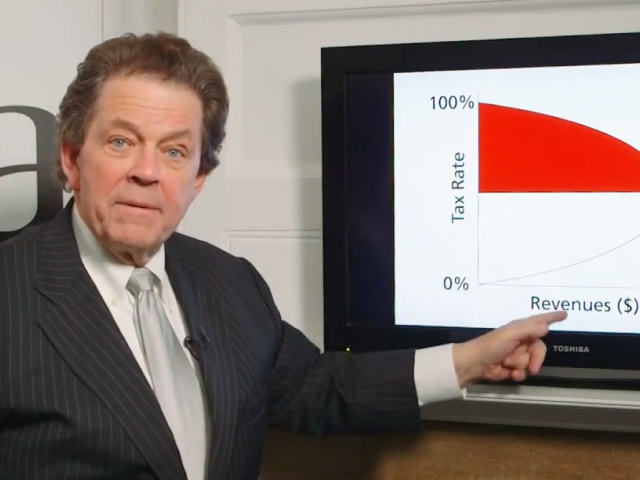

Following the Second World War, the most dramatic shift in the balance of tax power between the States and Commonwealth occurred.

In 1942, under the leadership of John Curtin as Prime Minister and Ben Chifley as Federal Treasurer, all income taxing authority was handed over to the Commonwealth by the States for the duration of the war under the defence power of the Constitution. This was intended to be temporary and to last for a year after the end of the war. However, while the war ended in 1945, the role of the Commonwealth as the sole income taxing authority did not.

For those concerned at the erosion of State rights through judicial activism, even worse was to come when, following the end of the Second World War, the High Court ruled that income tax collections could exist as an exclusive Commonwealth right under the normal powers of the Constitution.

Australia has the highest level of vertical fiscal imbalance of any federation in the world.

During the 1950s the State of Victoria mounted two legal challenges to the uniform tax legislation without success, and in 1959 at a Special Premiers’ Conference discussion of a return of income tax power to the States was on the agenda but could not be agreed. While there remains no legal barrier to the States exercising their right to levy income tax, there are practical (and political) reasons not to do so.

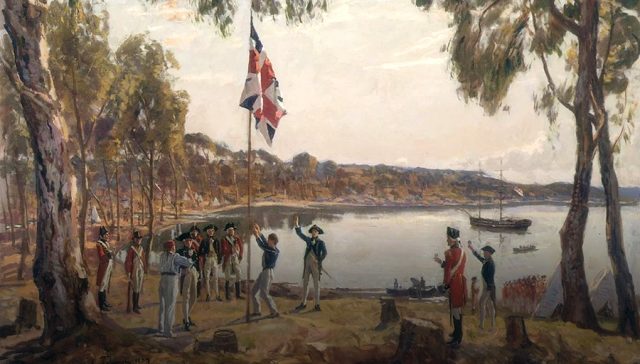

In the post war era, the centralisation of power continued to be affirmed through decisions of the High Court including the Franklin Dam case in 1988, the Queensland Rainforest case in 1989, Mabo in 1992, and the Wik Peoples case in 1996.

In speaking of the influence of the High Court and the threat to federalism arising from its decisions, Sir Harry Gibbs, former Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia said:

“It is a basic rule in the interpretation of any written document and indeed a matter of common sense that the whole document must be looked at in order to ascertain the meaning of any particular part. It might therefore have been supposed that in deciding on the meaning of the paragraphs of the Constitution which confer power on the Commonwealth Parliament, the Courts would have resolved any ambiguity by interpreting the provisions in a way that would maintain the federal distribution of power which the Constitution so obviously appears to guarantee ….. However, since 1920 the High Court has consistently rejected an approach of that kind.”

The struggle for power continued in the High Court in 2006 with the States challenging the Commonwealth over the validity of the federal WorkChoices legislation, which was enacted under the Corporations power. The High Court overwhelmingly came down in favour of the Commonwealth. While workplace relations laws, prior to the WorkChoices legislation, were a relic of a bygone era and desperately in need of reform, the rights of States in the area of industrial relations were now all but gone. For example, the 1999 decision of the High Court to allow SA State government public servants to be covered by a Federal Award undermined that State’s competitiveness.

The ability of a small, low cost-of-living State to use its industrial relations system to create a competitive edge over the larger States is important. South Australia, for example, under Premier Sir Thomas Playford, used this strategy (in conjunction with tariffs) to build a manufacturing base in Adelaide in the 1950s and 60s. Likewise Tasmania may wish to trade-off high salaries for quality of life and a green and clean environment.

The most dramatic shift in the balance of tax power between the States and Commonwealth occurred.

Undermining the rights of States is also evident in the actions of a burgeoning and, at times, arrogant Federal bureaucracy where the controlling hand of the Commonwealth is exercised through the terms and conditions embedded in funding arrangements with State government agencies.

Since federation the tax revenue balance has moved dramatically from the States to the Commonwealth. The imbalance that now exists, known as Vertical Fiscal Imbalance, has put the Commonwealth in an all-powerful position, able to dictate to the States how and where funds are spent.

Australia has the highest level of vertical fiscal imbalance of any federation in the world. The Federal government raises over 70% of all general government revenues, much more than is required to fund its own operations. The States raise just over half what they require to fund theirs. The balance of the States’ financial requirements is met through Commonwealth grants. This gives the Commonwealth enormous economic power and influence, and is inefficient and inequitable. It has the effect of keeping States like South Australia and Tasmania in a position of mendicancy.

Ideally, the States and the Commonwealth should only collect taxes for their own purposes with taxpayers and consumers fully informed as to what is a State tax and what is a Commonwealth tax. Those who spend the money should have the responsibility of raising it. It is about accountability, and governments of all persuasions should be specifically accountable for the money they raise and spend.

The use of Section 96 of the Australian Constitution, which empowers the Commonwealth to make grants to any State “on such terms and conditions as the Parliament thinks fit”, has been used by Federal governments to wield power over the States.

The Commonwealth’s control over State borrowings has further served to erode the power of States and their capacity to control their own destiny.

Got something to say?

Liberty Itch is Australia’s leading libertarian media outlet. Its stable of writers has promoted the cause of liberty and freedom across the economic and social spectrum through the publication of more than 300 quality articles.

Do you have something you’d like to say? If so, please send your contribution to editor@libertyitch.com

Bob’s contribution to the Australian community has been reflected in a wide range of appointments including National President of the Housing Industry Association, Co-Founder and Inaugural President of Independent Contractors of Australia, Director of The Centre for Independent Studies, and Senator for South Australia.