Who will watch the Watchers?

The Inspection House Principle

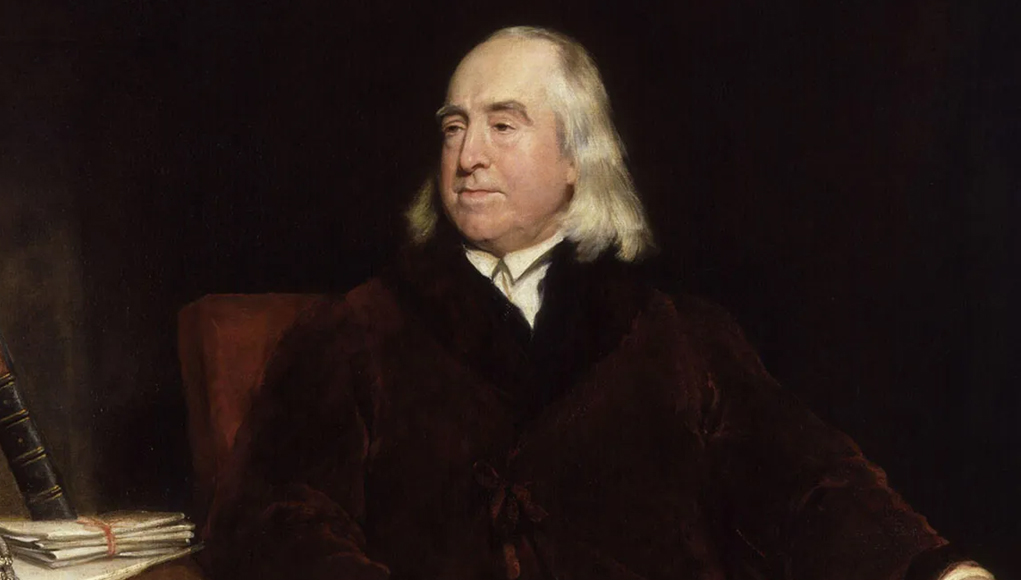

Curiosity for a deeper understanding of how Jeremy Bentham’s Inspection House principle relates to our current world has got the better of me. There is so much to dissect in the Panopticon that I thought it fitting to follow on from last month’s contribution.

At the end of his treatise, Bentham stresses that his principle of inspection should not be confused with that of spying, but rather, monitoring. He argues that those under surveillance must know they are subject to being watched, as this will result in producing the intended ideal outcome of: “morals reformed, health preserved, industry invigorated, instruction diffused, public burdens lightened, economy seated as it were upon a rock, the Gordian knot of the poor-laws not cut but untied…”

Yet, the detailing of his idea belies such an approach:

“It is obvious that, in all these instances, the more constantly the persons to be inspected are under the eyes of the persons who should inspect them, the more perfectly will the purpose of the establishment have been attained.”

Those who are incarcerated would be fully aware of being watched, in the same way we associate with the omnipotent eye of Big Brother. But to insist they will somehow be “kept in the loop” by their watchers is folly. Also, such an approach would merely produce robots rather than solve an unsolvable problem via the cutting of a Gordian knot.

There is no institution the globalists have left untouched in implementing their own Inspection House principle.

It is idealism on steroids to assert that those who you’ve incarcerated would always be kept abreast of your intentions and then expect to obtain the results referred to above. It is akin to today’s central planners – their intentions versus actions always at loggerheads.

This brings us to the question of who will watch those watching us?

Tyrannical-type characters have been waiting in the wings to exert their control over societies throughout history. At least in the ancient world there was a limit to how much territory those with power could seize; we are not so fortunate. The global entities of the UN, WEF, and WHO have gained a stronghold over the entire world. They work in lockstep with one another and with leaders of every nation – witness the coordinated pandemic response of 2020, still bearing fruit in 2024 via whipped up fear of new deadly viruses on the horizon – and predictions of global boiling ready to consume us in a fiery furnace.

Jeremy Bentham’s circular cell building arrangement of surveillance eerily mirrors what we are seeing planned today with 15-minute cities and herding of people from regional to urban areas. We are told it is to make life easier when it is just a foil to “monitor” us more closely.

Consider this final paragraph of Bentham’s Panopticon:

“What would you say, if by the gradual adoption and diversified application of this single principle, you should see a new scene of things spread itself over the face of civilised society?”

Between 1787 and 2024 his idea has indeed spread, gradually and fully over the face of civilisation.

Bentham refers to his principle as a “great and new invented instrument of government,” going on to define its excellence as the “great strength it is capable of giving to any institution it may be thought proper to apply it to.”

Stopping the spread requires parents and extended families to reclaim control over the raising of their children. It begins with the young, as they will be the future leaders and shapers of the world to come. No easy task when all around we see large, factory-like buildings being constructed for the sole purpose of “early learning.”

Bentham stresses that his principle of inspection should not be confused with that of spying, but rather, monitoring.

Reforming offenders in prisons is one thing, but schools are something else; at least, that’s what most of us would think. Yet, in Letter 21 of his treatise, Bentham raises the spectre of introducing “tyranny into the abodes of innocence and youth.”

Including the next generation in the need to be trained within a setting akin to reforming prisoners, reveals Bentham’s inclination to authoritarianism. Yet it is at this level that world rulers seek to manipulate and control. The current global ruling elite relish the idea of control, portraying it under the guise of moral reformation (much the same as Bentham), for example with health emergencies and restrictions cloaked in the narrative of keeping us safe.

Who better to inculcate a heart wrenching story into the minds of the young than those who seek to rob us of our freedoms and liberties? There is no institution the globalists have left untouched in implementing their own Inspection House principle. Have they managed to take Bentham’s blueprint to its natural conclusion? One may wonder at such a feat of horror.

But wonder, we must. When Bentham writes of a “simple idea of architecture” being the vehicle to improve morals, productivity and stabilise the economy, this does not necessarily mean a physical place, for in our world that would indicate our digital environment. We are already incarcerated inside our very own modern-day Panopticon, replete with watchmen on every digital corner.

Quis custodiet, ipsos custodes – Who will watch the watchers?

We must!

Gerardine is a Roman historian, with specific interest in Rome’s foundation up to the end of the Republic. She advocates that history gifts us with wisdom for the mind and nourishment for the soul, and keenly defends the ancients’ legacy of civic society, law, and government.