Reassessing Australian Judges’ Role in Hong Kong’s Court of Final Appeal (Part 1)

Historical Background

As an Australian legal practitioner with Hong Kong roots, I am compelled to address a critical issue: the participation of retired Australian judges in Hong Kong’s Court of Final Appeal.

Historically, overseas judges were included in Hong Kong’s judiciary to uphold judicial independence under the “One Country, Two Systems” principle established during the 1997 handover of Hong Kong from British to Chinese sovereignty. This allowed non-permanent judges from common law jurisdictions, including Australia, to serve on Hong Kong’s highest judicial body.

While some argue that the presence of overseas judges in Hong Kong’s Court of Final Appeal could help curb the erosion of civil liberties

Currently, four Australian judges serve in Hong Kong: The Honourable Justices Patrick Keane, Robert French, William Gummow, and James Allsop. They are invited to participate in hearings as needed, and their compensation is calculated on a pro-rata basis based on the monthly salary of a permanent judge of the Court of Final Appeal, currently approximately AUD $68,473. In recent years, two Australian judges have left: The Honourable Justice Murray Gleeson retired citing age in 2024, and Justice James Spigelman resigned following the enactment of the controversial National Security Law in Hong Kong 2020.

Recent developments in Hong Kong’s political landscape raise concerns about the continued viability and appropriateness of this arrangement. In this article, I argue that Australian judges should withdraw from serving in Hong Kong’s top court to preserve the integrity of the Australian legal profession and to avoid legitimising a system increasingly in direct conflict with judicial independence and human rights principles.

The Authoritarian Rules

The Hong Kong National Security Law (NSL) 2020 and the recently passed Article 23 legislation on national security (Art. 23) have significantly altered the landscape of human rights and the common law tradition in Hong Kong. The NSL empowers the Chief Executive of Hong Kong to handpick judges for political cases, undermining judicial independence, a cornerstone of the common law system.

Australian judges should withdraw from serving in Hong Kong’s top court to preserve the integrity of the Australian legal profession

Additionally, the NSL reverses the presumption of innocence in political cases, requiring the accused to prove they will not endanger national security to obtain bail. This has led to years of prolonged pre-trial detention for many high-profile Hong Kong dissidents. The NSL also permits the prosecution to request, and the court to allow, the elimination of juries in political cases, even those with potential life sentences, deviating from another fundamental common law tradition.

The draconian Art. 23 further erodes legal protections, allowing for detention of up to 16 days without access to a lawyer. It also grants the police authority to deny the use of specific lawyers or law firms for the accused. These developments represent a significant departure from established common law principles and raise serious concerns about the future of human rights and judicial independence in Hong Kong.

While some argue that the presence of overseas judges in Hong Kong’s Court of Final Appeal could help curb the erosion of civil liberties, their role is quite inadequate, or even irrelevant. The main reason for concern is that the Chief Executive has the power to exclude overseas judges from hearing political cases in the first place. In non-NSL cases involving civil and political rights presided over by Australian judges, their role has not significantly challenged the status quo or made substantial contributions to upholding human rights.

I will provide examples of these in the second part of this article.

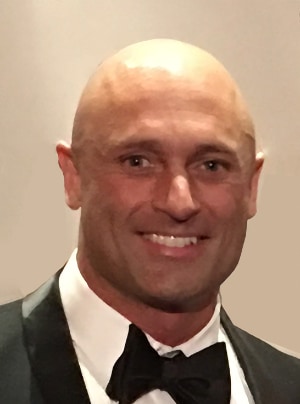

Ted Hui is a solicitor at RSA Law and former Member of the Hong Kong Legislative Council)