My 12 Years in Australia: Dreams, Doubts and Determination

The 30th of October marked my 12th anniversary in Australia. Twelve years ago, I left China — or more precisely, I escaped from China. I was extremely driven by a desire for freedom, following two life-changing years of struggle with Chinese authorities after speaking out against the authoritarian regime. I left in pursuit of freedom, better study opportunities, and the chance for personal growth.

In this article, I want to share my personal story, while also discussing its relevance to labour laws, national productivity, and personal finance.

I still remember the day I landed in Sydney. The sky was so blue, the air so fresh, and with every single breath I could smell freedom. I arrived with $2000 in cash, and after paying three months of rent upfront as a guarantee, along with the first month’s rent, I was left with just a couple of hundred dollars. My first place in Sydney was a tiny single room, no more than 8 sqm, in a shared house that cost me $150 a week, cash. My hard-working parents had paid for my tuition, and I was determined not to ask them for another cent for my living expenses. From that moment, I was on my own.

Every time the government imposes another tax, another restriction, another regulation,

it pushes society closer to the brink.

So I started looking for jobs. I found my first gig as a waiter just three days after arriving and started working on the first weekend. After that I worked multiple jobs, most of them off the books. The lowest-paying job I held earned me $8 per hour—half of the legal minimum wage. I worked over 40 hours a week, more than double the legal limit for a student visa holder, while pursuing a full-time Master’s degree at Macquarie University. If anyone wants to come after me or my former employers now, well, there are no records.

Looking back, those hard-working days are some of my fondest memories. But what I really want to say is that every time I hear politicians or the media talk about poverty, homelessness, or the need for more welfare to support minority groups, it disgusts me.

We need more Milei and less Marx.

Financially speaking, most Australians, whether rich or poor, are among the wealthiest 10% globally. Australia still enjoys a relatively free economy, with far less bureaucracy than most countries. Life here may not always be easy, but genuine poverty is rare unless one chooses to head down that path. I’ve often argued that a minimum wage is unnecessary; the market itself will set the minimum rate. In 2012-2013 I earned around $10 per hour, which many claimed was not a liveable wage. They were wrong. I survived through sheer hard work, labouring day and night, making muffins and donuts in the mornings, and working late shifts in restaurants. Not only did I survive, but I also managed to save. I bought my first car, a 1999 Toyota, for $1500 cash, and graduated in the top 10%.

Today, based on my conversations with small business owners, the market minimum wage is already close to $20 an hour, not far from the legal minimum. This is partly due to our poorly managed immigration system and disastrous COVID policies, both of which severely impacted labour markets.

A truly free market doesn’t need the government regulating wages, nor does it need laws dictating when a boss can or cannot contact employees (the so-called “right to disconnect”). Overly powerful, corrupt unions, under the guise of protecting workers, are suffocating the economy and severely limiting our freedom and productivity. In 2022 Australia ranked 16th out of 38 OECD countries in terms of labour productivity, and I would imagine we have further fallen behind in the last two years.

The sky was so blue, the air so fresh, and with every single breath I could smell freedom.

I’m genuinely grateful to all the employers who gave me opportunities when I was a freshly arrived young man with awkward-spoken English and barely any life skills. I worked, I learned, and I built a future. After completing my studies and a few uninspiring professional experiences, I launched my career as a mortgage broker. I started as a one-man operation, and today lead an award-winning top national brokerage team with over 30 brokers. Regrettably, I seldom hire anyone onshore; instead, I employ people offshore, as I am unwilling to navigate Australia’s complex labour laws or take the risks that some of my previous employers did to create opportunities for young or unskilled workers.

I was extremely driven by a desire for freedom, following two life-changing years of struggle with Chinese authorities after speaking out against the authoritarian regime.

The more I observe, the clearer it becomes that many laws and regulations are actively harming the economy. Take a recent example: NSW Revenue is attempting to apply payroll tax to companies like Uber and mortgage broking aggregators. The government despises self-employed people and businesses because they can’t control us. They want to grab every dollar they can from every hard-working individual who creates real value—whether it’s by driving a taxi or providing mortgage services.

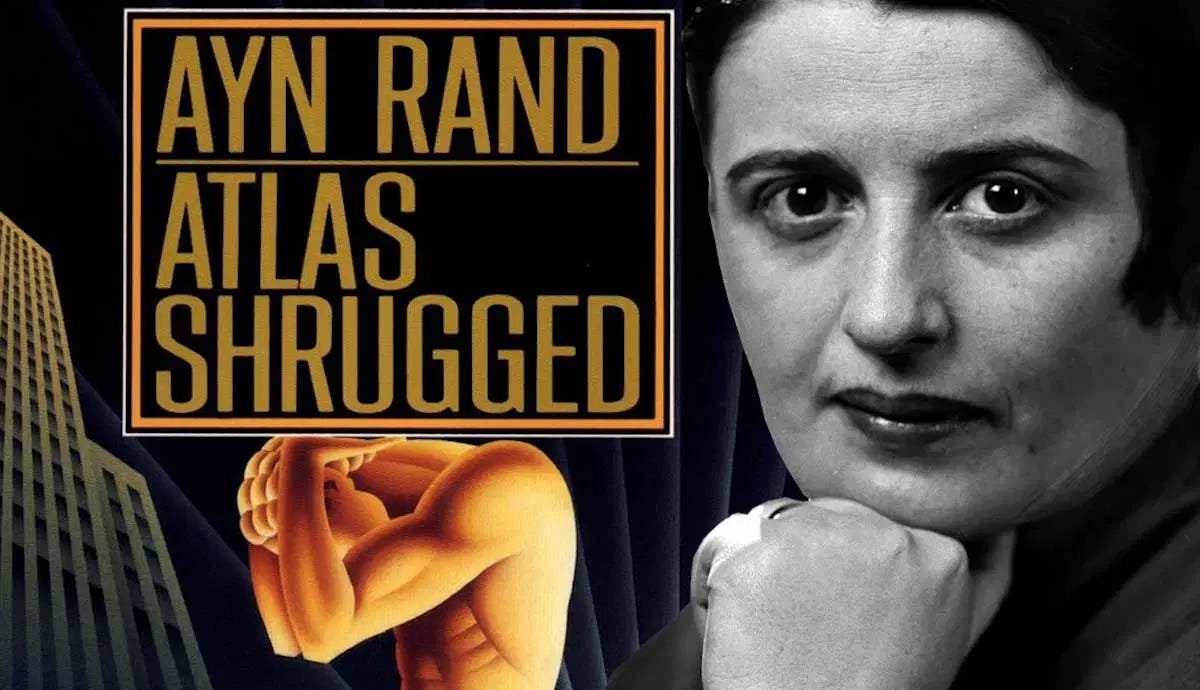

In Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged, John Galt’s final speech warned of the collapse of society if entrepreneurs, creators, and employers were to go on strike. This is not far from the truth. Every time the government imposes another tax, another restriction, another regulation, they are pushing society closer to the brink. If innovators, business owners, and workers stop creating, producing, and striving for excellence, the whole system collapses.

We don’t need more welfare. We need a freer economy. We need more Milei and less Marx. Australia became a prosperous nation because of freedom, not because of regulations. The more the government meddles, the more it stifles the potential for everyone.

Over my 12 years in Australia, I’ve experienced moments of frustration—particularly with the country’s COVID policies and its tendency to copy the authoritarian policies of the nation I left behind. Despite these setbacks, I remain optimistic. I look forward to a future where Australia embraces more freedom, becoming the country I once dreamed of—a place that inspires and attracts those who cherish liberty.