The New Gulag

In his famous three-volume masterpiece, The Gulag Archipelago, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn described the frozen wastelands of Siberia where political prisoners and dissidents the Soviet state considered dangerous were held (for their speech, not their actions). A gulag was a Soviet prison; an archipelago is a string of islands; hence the term ‘gulag archipelago’ – a string of camps, prisons, transit centres, secret police, informers, spies and interrogators across Siberia.

Today, people are frozen out of society in more subtle ways. The authorities no longer bash down your door and haul you off to a gulag for espousing the ‘wrong views’; instead, they silence and freeze you out of existence in other ways.

No-one describes the current situation better than Scottish commentator Neil Oliver in his Essentials of Life video clip here. More about that shortly.

Divide and conquer

As we know, the Left’s chief weapon is division. Unite the disaffected groups and those with grievances, and then ‘divide and conquer’ the rest of us. Divide along racial, generational, sexual, religious or economic lines. Any line will do.

What may have started as ‘the workers vs the bosses’ – ‘the proletariat vs the bourgeoisie’ – and ‘supporting the poor’, became just a ruse to gain power. Workers and the poor have long since been abandoned by the Left who now find other ways to divide and conquer.

In his excellent book, Democracy in a Divided Australia, Matthew Lesh writes:

“Australia has a new political, cultural, and economic elite. The class divides of yesteryear have been replaced by new divisions between Inners and Outers. This divide is ripping apart our political parties, national debate, and social fabric.

Inners are highly educated inner-city progressive cosmopolitans who value change, diversity, and self-actualisation. Inners, despite being a minority, dominate politics on both sides, the bureaucracy, universities, civil society, corporates, and the media. They have created a society ruled by educated elites – that is, ruled by themselves.

Outers are the instinctive traditionalists who value stability, safety, and unity. Outers are politically, culturally, and economically marginalised in today’s graduate-dominated knowledge society era. Their voice is muzzled in public debate, driving disillusionment with the major parties, and record levels of frustration, disengagement, and pessimism.“

For over a hundred years, Australia fought to remove race from civic considerations. Yet now we are being asked to permanently divide the nation by entrenching an Indigenous Voice into our Constitution. By the ‘Inners’, of course.

In the workplace, politicians are still treating workplace behaviour like a game of football. Australia’s employers (‘the bosses’) are on one team, and Australia’s employees (‘the workers’) are on the other. The game is then overseen by a so-called ‘independent umpire’ called the Fair Work Commission. But of course, this is not how workplaces operate at all. The ‘game’, if you even want to call it that, is played not by two teams of employers and employees, but by hundreds, even thousands of different teams, competing against hundreds and thousands of other teams of employers and employees.

Mark Twain observed, “Few things are harder to put up with than the annoyance of a good example”.

Here’s one – the infamous Dollar Sweets dispute where unions were picketing Fred Stauder’s confectionery business. Other confectionery businesses were approached to support Fred but were rebuffed saying, “Why should we care if Dollar Sweets goes down? It will mean more business for us.” So much for ‘bosses vs workers’.

While paying lip service to free markets, property rights, personal responsibility, self-reliance, free speech, lower taxes, the rule of law and smaller government, the Liberal Party in Australia has all but abandoned these ideals in practice. As has big business, which, truth be known, was never on the side of free markets. Corporations have always wanted markets they can dominate, and to eliminate the competition. If that means aligning with the Left or doing the government’s bidding, so be it.

Which includes – and here we return to our ‘new gulags’ theme – closing a person’s bank account, destroying them on social media, or excluding them from employment. Business is right on board with this.

The Left will keep pushing its woke agenda until it is stopped. And it will not be stopped with facts, figures, logic, evidence or reason. It doesn’t care about any of that. It will only be stopped with political power.

Holding conferences, writing opinion pieces, producing podcasts and YouTube interviews in the hope of persuading people have, I’m afraid, had their day. The ‘Inners’ now rule.

Stopping the relentless march of the Left will require political power. Seats in parliament. Which means like-minded people and parties forming alliances and working strategically and tactically together to win seats.

In Neil Oliver’s video clip, he says, “When it comes to the state, that which it can do, it certainly will do” and “What can happen to anyone, will soon happen to everyone”.

So, if you belong to a think-tank, lobby group or centre-right political party, and want to stop the woke Left further ruining our country, then please encourage your organisation to place less emphasis on winning arguments and more emphasis on winning seats – as previously outlined here and here.

Thank you for your support.

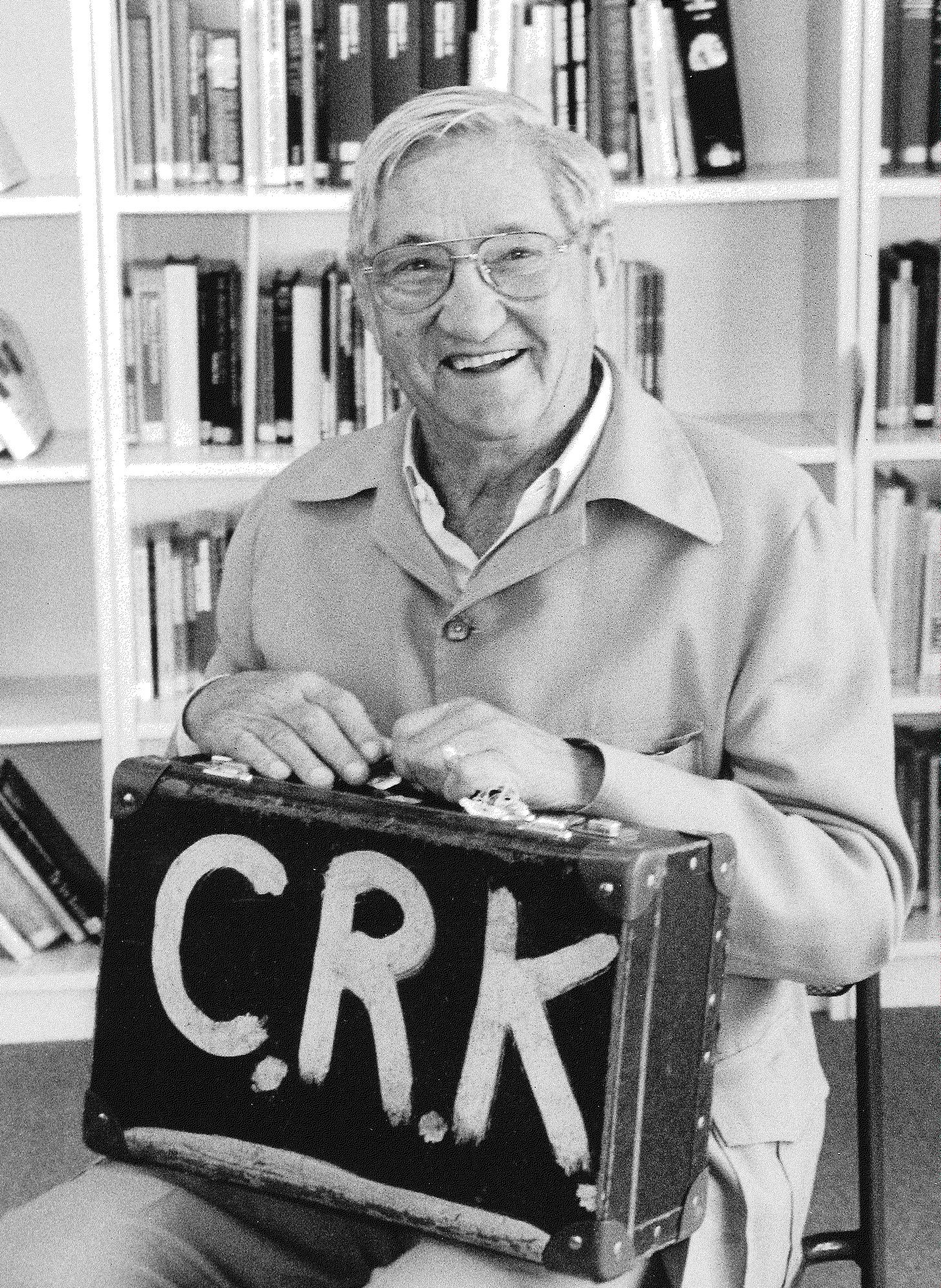

Bob’s contribution to the Australian community has been reflected in a wide range of appointments including National President of the Housing Industry Association, Co-Founder and Inaugural President of Independent Contractors of Australia, Director of The Centre for Independent Studies, and Senator for South Australia.