Argentina Elected A Libertarian Leader, And It Could Happen Here

But it probably won’t.

Argentinians recently voted in Javier Milei to be their President.

Milei has good policies, and he will probably be able to implement a good chunk of them.

This is not just good for Argentinians, it is good news for us. Having a libertarian doing libertarian things in Argentina will bolster the credibility of libertarian policies and parties in Australia.

But we shouldn’t get carried away. Milei will not be able to implement all of his policy wish list, and not all of his policies are good. And the circumstances of Milei’s election won’t be repeated in Australia any time soon.

Milei has good policies.

Milei’s party has an exemplary, wide-ranging, libertarian platform promoting both social and economic freedoms. Milei did not appear to walk away from any of this platform in his campaign.

The campaign naturally focussed on economics, given Argentina’s current crisis. In his campaigning Milei skilfully educated voters on why a libertarian prescription on monetary, fiscal, and regulatory policy is the way to go.

The lack of judicial independence has severely eroded limits on government

Milei is likely to be able to implement some of his policies.

The formal powers of the Argentinian President are similar to those of the US President, with appointment, veto, and decree powers.

Unlike US Presidents, Argentinian Presidents are in the habit of regularly introducing a budget, so Milei will be better placed to cut government spending than an American President.

Milei will bolster the credibility of libertarian parties in Australia.

We can now point to a libertarian in power in a country with more than 45 million people.

We now have a great counter-point to claims that libertarianism is irrelevant.

Australian libertarians seeking election will be able to say that if libertarians can be elected, and if libertarian policies can be implemented in Argentina, then the same can happen in Australia.

But not all of Milei’s policies are good.

Milei stoked and tapped into anti-woke sentiment, including through supportive references to America’s Trump and Brazil’s Bolsonaro.

This is a problem if it translates into the implementation of illiberal policies, or concentrating on issues of wokeness at the expense of more crucial reform, or if it means Milei has the same regard for the law as Trump and Bolsonaro.

Having a libertarian doing libertarian things in Argentina will bolster the credibility of libertarian policies and parties in Australia.

That said, Milei’s comments cleverly tapped into anti-woke sentiment without committing to do anything illiberal. After all, there’s nothing illiberal about abolishing a Women’s Ministry. So there might be nothing to worry about on this score.

A more clearly disappointing campaign tactic was Milei’s opposition to legalising euthanasia.

But this tactic may well have been a smart move. A large proportion of Argentinians claim to be Catholic, and the Catholic Church is staunchly anti-euthanasia. Argentinian politics, even for presidential elections, involves considerable coalition building, with Milei’s party working with Argentina’s Faith Party. Milei also faced significant criticism from the Church for wanting to slash welfare, so perhaps it was best to concentrate the attack on the Church at its weakest point.

Milei will not be able to implement all of his policy wish-list.

Milei’s alliance of parties will have 38 of the 257 seats in the lower house of the national parliament, and 7 of the 72 seats in the upper house.

Argentina is a federal country, and there is next to no libertarian presence at Argentina’s provincial level.

Many of the circumstances of Milei’s election will not be replicated in Australia.

It seems that Milei was elected because both the traditional left-wing grouping (who were in government) and the traditional right-wing grouping (who were in opposition) were unusually splintered and unpopular. Both groupings also lacked a charismatic leader, with both the incumbent President and Vice President not contesting the election. Such conditions could occur in Australia.

But the main reason Milei was elected was Argentina’s economic malaise. Argentina currently has one of the highest inflation rates in the world, and its economy is shrinking. The latest assessment of Freedom House is damning:

“Aggravated by corruption and political interference, the lack of judicial independence has severely eroded limits on government. Leftist spending measures and price controls distort markets, and government interference still hobbles the financial sector. Fading confidence in the government’s determination to promote or even sustain open markets has discouraged entrepreneurship.”

Freedom House’s assessment of Australia is glowing in comparison.

So Argentina needs a libertarian leader more than Australia does, and hopefully more than Australia ever will.

Milei’s election does not presage a global wave of libertarianism, but it is still great news, not just for Argentinians, but for Australians too. Let’s watch and learn.

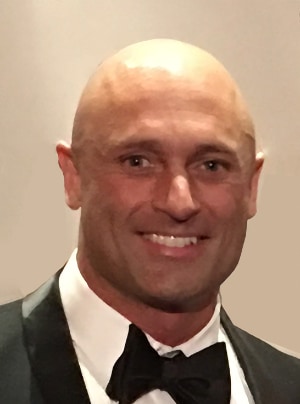

Duncan Spender is CEO of Oysters Tasmania, having previously served as CEO of the Multicultural Council of Tasmania. He advised Senator David Leyonhjelm from 2014 and briefly served as Senator in 2019. Duncan’s early career was in local government and the Australian and New Zealand Treasury Departments.